By Partner Carlie Holt, Senior Associate Susan Withycombe-Taperell and Lawyer Layla Langridge

Thursday, 22 June, 2017

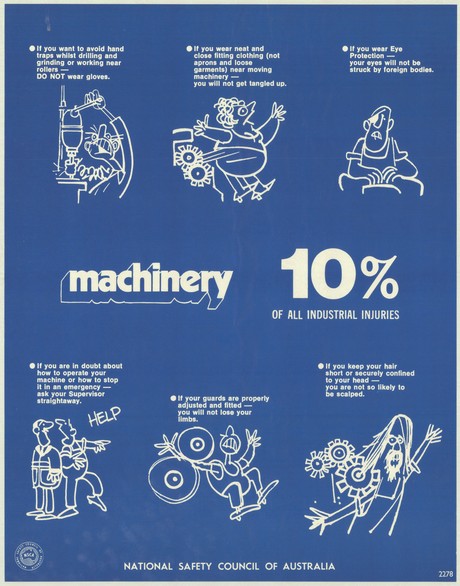

Our limbs and appendages are (un)surprisingly susceptible to injuries caused by machinery and equipment, commonly referred to as ‘plant’, in Australian workplaces. All too often, we see plant injuries become fatalities. In this article, we provide a straightforward guide to your obligations and best practice for ensuring workplace safety around machinery, to minimise the risk of serious harm in the workplace.

Whose responsibility is machine safety?

Under the harmonised Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Cth) and Work Health and Safety Regulation 2011 (Cth) (WHS laws), a person conducting a business or undertaking (PCBU) must ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health and safety of workers. This includes providing and maintaining safe plant, establishing safe systems of work and ensuring the safe use, handling and storage of plant. In addition, the WHS laws impose health and safety duties on designers, manufacturers, suppliers and importers of plant, often referred to as ‘upstream’ duty holders, because of the potential for their acts or omissions to impact PCBUs, workers or members of the public who encounter their plant in workplaces ‘downstream’.

WHS laws also impose similar duties of care on officers, workers, persons controlling a workplace and those with other similar roles, to ensure the safety of workers in the workplace so far as is reasonably practicable.

The persons to whom these duties are owed are ‘workers’ — employees, contractors, subcontractors, employees of labour hire companies, apprentices, trainees, work experience students and volunteers.

Can I delegate my duties?

Duties cannot be delegated to others. It’s important to note that more than one person or PCBU may concurrently hold an obligation to ensure the safety of workers and, in this situation, each person with the duty must consult, cooperate and coordinate activities with all other persons who have a concurrent duty so far as reasonably practicable.

The concurrent, non-delegable nature of WHS duties was highlighted last year when the District Court of New South Wales fined a principal contractor and expert subcontractor $300,000 and $225,000, respectively, for the fatal injury of a labour hire worker in SafeWork NSW v Ceerose Pty Ltd [2016] NSWDC 184; SafeWork NSW v DSF Constructions Pty Ltd [2016] NSWDC 183. The principal contractor argued it was less culpable because of the subcontractor’s “extensive failures” concerning the foreseeability of the risk (the worker was working directly under a crane). It was held that despite the subcontractor’s role as an expert contractor providing full-time supervision and coordination of the work being undertaken, the principal contractor had an overriding responsibility for safety on the site and still had to discharge its WHS duties.

How can I reduce the risk of incidents?

Under the WHS laws, each jurisdiction approves codes of practice (CoP) that are admissible in court proceedings to demonstrate what is known about hazards, risks or controls, and can evidence what is reasonably practicable in managing WHS risks and incidents. In 2016, Safe Work Australia published the model CoP ‘Managing Risks of Plant in the Workplace’, which has been adopted by the harmonised jurisdictions and sets out an easy-to-follow risk management process:

- Identify hazards;

- Assess risks arising from hazards; and

- Eliminate or, where not reasonably practicable, control risks using the hierarchy of control.

Practical steps for eliminating or controlling risks of machinery-related injuries

Get familiar with Australian Standards, CoP and manufacturer manuals

Australian Standards provide guidance on relevant safety matters, including the use of plant, and (like a CoP) may be helpful in determining what is reasonably practicable. Australian Standards must be complied with if specifically referred to in WHS laws, even if compliance with the Standard is not otherwise mandatory.

In 2016, a PCBU was fined $75,000 by the District Court of NSW in WorkCover Authority of NSW v Karemen Pty Ltd [2016] NSWDC 201 for a fatal incident that occurred in their workplace, where a two-post hoist moved while a motor mechanic was working under a car. The Australian Standard for vehicle hoists is that a lock must be incorporated on the hoist to prevent supporting arms from moving. In addition, the hoist manufacturer’s manual recommended daily checks to ensure it was functioning correctly and a safety alert had been issued the year before by the Western Australian regulator in respect of a similar fatal incident involving a two-post hoist. Taking this all into account, the court found “the risk in this case was plainly foreseeable and so was the incident”, which reaffirms the importance of understanding obligations under Australian Standards, compliance with plant manual instructions and keeping abreast of relevant safety alerts.

Ensure compliance with manufacturing standards

In 2016, a South Australian timber company was fined $57,000 for a serious injury to a worker’s hand. A manager and the worker had undertaken a risk assessment of a table saw and removed the guarding after deciding it was of poor quality and potentially a safety hazard. The guarding was replaced with a sign — ‘Keep hands clear of blade’. This was contrary to the instruction manual, which required the side and top saw guards to remain fitted and maintained. In failing to comply with the manufacturing standard, the worker was subsequently injured when coming into contact with the saw.

Organisations should always consult with manufacturers to ensure a machine can still operate in a safe and effective manner before removing guard railings or any other safety feature. Modifications to machinery should be carefully considered to ensure these do not increase or pose further risks to health and safety.

Only use safe and up-to-date equipment that is regularly audited

All equipment should be regularly maintained and kept up to date with industry and Australian Standards. Machinery should be regularly audited to ensure compliance with WHS laws and CoP. Many machine manufacturers offer auditing services, some regulator websites include audit tools and there are a number of consulting businesses that perform audits.

Provide workers with adequate and regularly updated training

It is not sufficient to provide a worker with induction training only. Following an incident, companies often discover that employees failed to implement procedures they were trained in or they were taking shortcuts. Workers should receive refresher training at appropriate intervals to ensure their knowledge is up to date and that they are properly following the company’s procedures.

Keep policies, procedures and training updated to reflect new plant

Not all plant is the same. It is important to regularly review and update policies and procedures, and provide training when new plant is introduced. This year, the decision of Perkins v Woolworths Pty Ltd [2017] QDC 1 reiterated the importance of this when an injured worker commenced civil proceedings against his employer and was awarded more than $650,000 in damages. The worker’s injury occurred when the plant normally used (and for which the plaintiff received training) became inoperable and a replacement plant with slightly different features was used. The worker was not provided with any instruction or training on the new plant and so the company was found to have breached its common law duty of care.

Implement the highest level of control

WHS laws require all risks to be eliminated. Where this is not reasonably practicable, risks must be minimised in line with the hierarchy of controls to manage those risks.

In 2016, a mining company was convicted and fined $75,000 after a worker was fatally crushed between a pinch point in a mine shaft in the decision of Inspector Nash v MacMahon Mining Services Pty Ltd (re Junk) [2016] NSWDC 171. At the time of the incident, the PCBU relied on a written procedure to control the risk, which included a caution to keep body parts inside the machinery. However, the procedure also required workers to lean out over the edge to assess the distance from the platform, exposing workers to the risk of pinch points.

The court found that a higher level of control should have been implemented, such as the use of mesh webbing, signals and alarms. These controls had not been considered at the time of the incident or at the time the procedure was drafted. This case highlights the importance of continually reviewing procedures to ensure they are up to date and reflect developments in technology or industry standards.

Ensure policies and procedures are followed at all times

The case of Russell v Leonhard Kurz (Aust) Pty Ltd [2015] SAIRC 13 in South Australia saw a PCBU fined $42,000 after a worker sustained severe injuries when her gloved hand was caught in machinery. The PCBU allowed the worker to operate the machinery while wearing gloves, despite a near miss with the same employee four years before.

The PCBU’s position was that it had advised the employee not to wear the glove after the first incident. However, it did not formally direct her not to do so and even provided her with a glove when asked. During sentencing, the PCBU acknowledged it should have directed the employee to remove the glove, enforced its safety practices and ensured the worker was operating the machinery in compliance with the manufacturer’s manual.

Encourage reporting of near misses

Workers should be encouraged to report near-miss incidents. Regular reporting ensures processes and procedures are updated and strengthened. Employers should know what their near-miss rate is and managers should encourage open communication with workers about safety concerns. Workers should feel comfortable raising safety issues without fear of discrimination.

Consult with workers

Consulting with workers and improving organisational communication can reduce the risk of injuries and improve your workplace safety culture. Consultation, including meeting with, talking to and observing workers, can assist a PCBU to identify gaps in processes and procedures as well as any areas of the business that don’t meet regulatory requirements.

Once consulted, updating processes accordingly can alleviate safety concerns, build trust in the organisation and result in fewer incidents for workers.

Walking the talk

It is very difficult to identify and eliminate every possible risk of a machinery incident in the workplace; however, taking the above steps and ‘walking the talk’ when it comes to safety will decrease the risk of plant-related injuries and increase your prospects of successfully defending any charges if an incident does occur.

Supporting the wellbeing of Australia's firefighters

Academics Dr DAVID LAWRENCE and WAVNE RIKKERS detail their continuing research in the area of...

Software-based COVID-19 controls help protect onsite workers

The solution decreases COVID-19-related risks by ensuring that contractors and visitors are...

Spatial distancing rules: are they insufficient for health workers?

Researchers have revealed that the recommended 1- to 2-metre spatial distancing rule may not be...